A child’s tooth found in a French cave is the oldest known evidence of the existence of modern humans in Western Europe. The tooth fragment suggests that our ancestors were evolving in place at least 54,000 years ago, about 10,000 years earlier than previously thought.

The oldest fossils of early modern humans outside of Africa have been found in Israel, dating from 194,000 to 177,000 years ago, and possibly in Greece, dating to around 210,000 years ago. The Levant is traditionally believed to have played a fundamental role in the dispersal of our ancestors, although the Late Pleistocene paleoanthropological records of this region are still debated. In Europe, however, their appearance seems to have occurred much later, perhaps because of ecological barriers and/or the occupation of the region by Neanderthals.

Until now, the earliest evidence for the establishment of Homo sapiens in Europe was limited to around 45,000 to 43,000 years ago based on five isolated dental remains in three Italian sites. On the other hand, the last Neanderthal remains in Europe are dated to 42,000 to 40,000 years ago. In reality, our species was present there long before that.

A tooth that changes everything

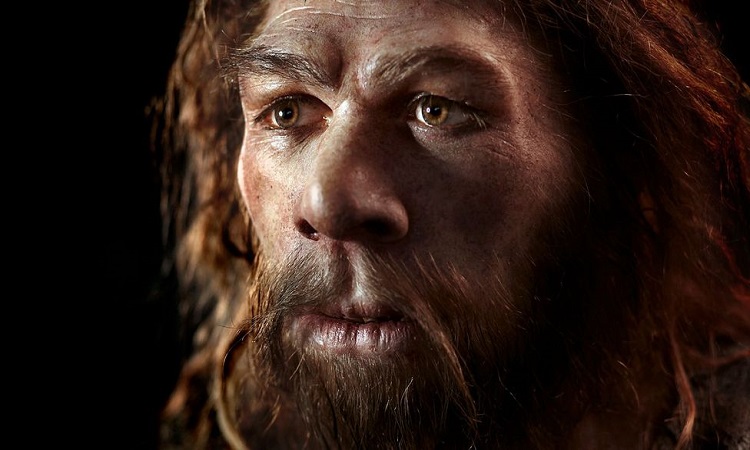

The Grotte Mandrin, in the Rhone Valley, once housed successive groups of Neanderthals and Homo sapiens. A fresh look at the remains of this rock shelter, however, reveals a much more complicated story.

As part of recent work, researchers have indeed come across the dental remains of at least seven individuals found in a dozen archaeological layers, each of them representing a different period. After analysis, it emerged that six of these individuals were Neanderthals. In contrast, one of the fossil molars appears to belong to a modern human child from around 54,000 years ago.

Many population overlaps

Not only does the age of this child’s tooth push our species’ presence back to the region by around 10,000 years, but this human remains was also believed to have been discovered in a layer sandwiched between two Neanderthal layers.

Researchers had long suspected that this rock shelter was a meeting place between Neanderthals and modern humans. Researchers have indeed spent more than thirty years carefully sifting through the layers of earth inside the cave, unearthing hundreds of thousands of artifacts used by both populations. We also know that humans and Neanderthals interbred extensively. However, this new study does not suggest cultural exchanges, but rather a clear overlap between the two species. In other words, Neanderthal and modern human populations have replaced each other several times in the same territory. In one case, the cave even changed hands within about a year.

Whatever the reason for these overlaps, this new work published in Science Advances is sure to spark new conversations about humanity’s migration to the Old Continent.

Email: ben@satprwire.com Phone: +44 20 4732 1985

Ben has been listening to the technology news for quite some time that he needs just a single read to get an idea surrounding the topic. Ben is our go-to choice for in-depth reviews as well as the normal articles we cover on a normal basis.